Novel Therapies Expand Hypogonadism Treatment Options

RELEASE DATE

January 1, 2025

EXPIRATION DATE

January 31, 2027

FACULTY

Debra L. Stevens, PharmD, BCPP

Associate Professor

Department of Pharmacy Practice

Southwestern Oklahoma State University College of Pharmacy

Weatherford, Oklahoma

Tiffany Kessler, PharmD, BCPS

Professor

Department of Pharmacy Practice

Southwestern Oklahoma State University College of Pharmacy

Weatherford, Oklahoma

Brooke L. Gildon, PharmD, BCPS, BCPPS, FPPA

Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice

Southwestern Oklahoma State University College of Pharmacy

Weatherford, Oklahoma

FACULTY DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

Drs. Stevens, Kessler, and Gildon have no actual or potential conflicts of interest in relation to this activity.

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC does not view the existence of relationships as an implication of bias or that the value of the material is decreased. The content of the activity was planned to be balanced, objective, and scientifically rigorous. Occasionally, authors may express opinions that represent their own viewpoint. Conclusions drawn by participants should be derived from objective analysis of scientific data.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Pharmacy

Pharmacy

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education.

UAN: 0430-0000-25-005-H01-P

Credits: 2.0 hours (0.20 ceu)

Type of Activity: Knowledge

TARGET AUDIENCE

This accredited activity is targeted to pharmacists. Estimated time to complete this activity is 120 minutes.

Exam processing and other inquiries to:

CE Customer Service: (800) 825-4696 or cecustomerservice@powerpak.com

DISCLAIMER

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patients’ conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

GOAL

To identify the various types of dementia, highlight current management and treatment options, and recognize the behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia.

OBJECTIVES

After completing this activity, the participant should be able to:

- List the four most common dementia types

- Define the typical onset, course, and life expectancy of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia.

- Describe the mechanism of action, dosing, administration, and adverse event profiles of current therapies for Alzheimer’s disease.

- Identify a treatment and monitoring plan for cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric symptoms in a patient with dementia.

ABSTRACT: Dementia is an increasing condition in persons aged older than 65 years in the United States and worldwide. Types of dementia include Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia, as well as some rare conditions. Pharmacologic treatment, depending on the type, may include cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. Antiamyloid monoclonal antibodies are the newest agents that are specifically indicated for Alzheimer’s disease. Many patients with dementia also exhibit neuropsychiatric symptoms, which may require drug treatment, including atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics despite their black box warning in this population. Many opportunities for intervention by the pharmacist include preventive measures, pharmacologic treatment, and deprescribing medications that may be worsening symptoms.

Dementia is a global problem, with estimates indicating that approximately 153 million persons may be diagnosed with this disease worldwide by 2050.1 In the United States, it is estimated that 6.7 million persons are living with dementia, with projections for these numbers to increase to 14 million by 2060.2 Dementia is a term that encompasses many different neurodegenerative diseases with various pathologic mechanisms. The most common cause is Alzheimer’s disease (AD).3 Other dementia causes include vascular, frontotemporal, and Lewy body, as well as some less frequently diagnosed diseases.3 Dementia increases with age, with a prevalence as high as 35% in those aged older than 90 years.3 The cost of dementia care in the U.S. in 2024 is estimated to be $360 billion and is expected to increase in the future.4

Dementia is defined as a loss of cognitive abilities in at least two domains (language, visuospatial, executive) that affects daily functioning.5 It is differentiated from mild cognitive impairment, which is defined as a decline in performance on neuropsychological tests while maintaining daily functions.5 Some, but not all, individuals who are diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment will eventually progress to dementia. Many cognitive assessments can be performed to evaluate for dementia, including the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the Mini-Mental State Examination.6 Neuropsychological testing as well as brain imaging may be utilized to identify the specific type of dementia.6 A detailed review of these assessments is beyond the scope of this review.

COMMON TYPES OF DEMENTIA

The variable manifestations of dementia help to attri bute the cause and identify the type of dementia present. The four most common dementia types are AD, vascu lar dementia (i.e., cerebrovascular disease), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

Other, more rare conditions that cause dementia or dementia-like symptoms have also been identified.7 These include the following: normal pressure hydro cephalus, an abnormal buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain; Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a rare brain disorder; Huntington’s disease, an inherited, pro gressive brain disorder; chronic traumatic encepha lopathy, caused by repetitive traumatic brain injury; HIV-associated dementia, in which HIV spreads to the brain; Parkinson’s dementia, wherein changes in think ing and behavior start after a Parkinson’s disease diag nosis; limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 enceph alopathy, mostly impacting those aged older than 80 years and caused by abnormal clusters of the TDP-43 protein; cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, an inherited type of vascular dementia caused by a faulty gene; progressive supranuclear palsy, which causes both dementia and palsy or movement-related prob lems; and corticobasal syndrome, dementia with com pounded challenges of visual perception.7

To make defining a dementia type even more challenging, mixed dementia is also commonly seen. This highlights the importance of identifying conditions that are likely to contribute to a dementia diagnosis.

Alzheimer’s Disease

AD is the most common type of dementia. The initial cognitive domains impacted in AD are short-term recall and orientation with brain-related changes that include accumulation of β-amyloid and tau proteins and hippocampal atrophy.8,9 The onset and course of AD are slow and gradual over months to years, with a typical age of onset at or after 65 years.5,10 The classic presenting symptom is short-term memory loss with sporadic memory impairment accompanied by other subtle cognitive deficits (e.g., visuospatial problems, word-finding challenges, and impaired reasoning). The impact on memory in AD is progressive and in reverse chronological order, meaning that these patients lose recent recall first with the ability to remember early life events well. Carriers of the apolipoprotein E4 gene have a greater risk of AD advancement, yet this genetic marker is not predictive. The life expectancy after an AD diagnosis varies but is about 10 years from symptom onset.

Vascular Dementia

The prevalence of vascular dementia is on the rise due to increasing rates of stroke and cardiovascular disease. Initial cognitive domains impacted in vascular dementia vary from person-to-person, but loss typically correlates with the cognitive role of the infarcted area.8,9 Brain-related changes seen initially are increases in β-amyloid and damage to the area(s) of obstruction. The onset and course of vascular dementia are determined by the timing of an acute vascular event.5,10 Cognitive impairment can occur within minutes or days of a stroke, for example. The course is often described as stepwise. The disease may also progress if or when further cardiovascular insults occur. Understanding and controlling vascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) and prior vascular events (e.g., myocardial infarction) are imperative when caring for patients with vascular dementia. Of distinct importance, vascular dementia has the potential for symptom improvement as the brain recovers.11

Dementia With Lewy Bodies

DLB can be challenging to diagnose, with early symptoms presenting like those of other brain or psychiatric disorders. Core symptoms include variable cognition, visual hallucinations, rapid eye movement behavior disorder, and parkinsonian symptoms.10 The initial cognitive domains impacted in DLB are visuospatial and executive function with brain-related changes of accumulation of α-synuclein.8,9 Pathologic characteristics may also include generalized brain atrophy. The onset and course of DLB are slow and gradual, spanning months to years.5,10 Furthermore, there can be fluctuations in levels of alertness and cognition leading to better or worse days for the patient. The timing of symptom onset is imperative to differentiate DLB from Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD).10 If all core symptoms are present within 1 year, then DLB is diagnosed. If parkinsonian symptoms occur first for at least 1 year, the diagnosis is PDD. Both types are caused by Lewy body accumulation. The life expectancy of a patient with DLB is typically less than 10 years.

Frontotemporal Dementia

FTD occurs earlier in life (age 45-65 years) and tends to progress rapidly, with more than 60% of cases being genetically linked.10,11 The initial cognitive domains impacted in FTD are naming and repetition, with brain-related changes of atrophy of frontal and/or temporal lobes.8,9 Patients who are diagnosed with FTD often show marked changes in behavior (e.g., disinhibition, apathy), language (e.g., semantic paraphasia), and executive function problems, with early relative preservation of memory.5 Loss of the temporal lobe influences impulse control and can trigger failure of the ability to differentiate right from wrong. Difficulty controlling or managing behaviors is defined as behavioral variant FTD. The life expectancy of patients with FTD varies significantly, with some sources listing this as less than 5 years due to the rapid, progressive nature of the disease.10

PREVENTION

Modifiable risk factors to prevent and delay the development of dementia have been identified, and reducing these risk factors could prevent approximately 40% of dementia cases. These risks include less education, loss of hearing, traumatic brain injury, hypertension, alcohol use (>12 units/week), obesity, smoking, depression, social isolation, physical inactivity, diabetes, air pollution, vision loss, and elevated LDL cholesterol. Multiple risks may be present in an individual, and interventions for all applicable risks should occur to maximize the prevention benefit. Interventions to reduce or modify risks should be instituted early and continued throughout life.12 Data exist for additional interventions, which include diet, sleep, delirium prevention, and multifactorial interventions to reduce risk or improve cognition.3

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Before initiating pharmacologic treatment, a thorough medication review should occur to evaluate for medications that may be contributing to decreased cognition. At least one medication with anticholinergic effects is prescribed in 20% to 50% of older adults. These medications can be problematic due to their effects of dizziness, confusion, sedation, and blurred vision, which can result in a decline in cognitive and physical function. There is an association with a decline in cognition and additive anticholinergic load.13 The American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria recommend that the use of more than two medications with anticholinergic properties should be avoided.14 OTC medications in this category include diphenhydramine, doxylamine, oxybutynin, and histamine type 2 receptor antagonists.10,14

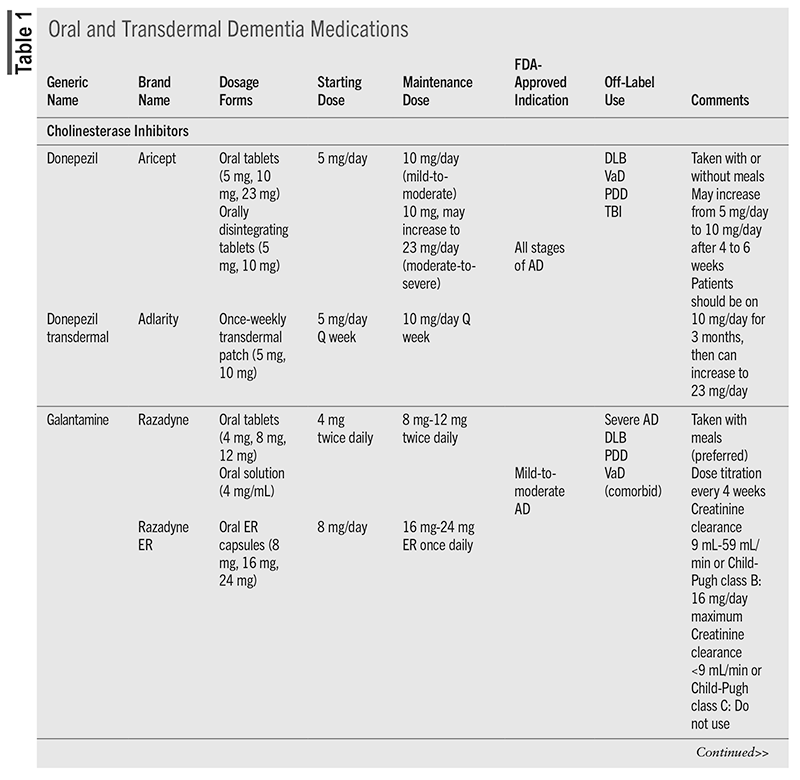

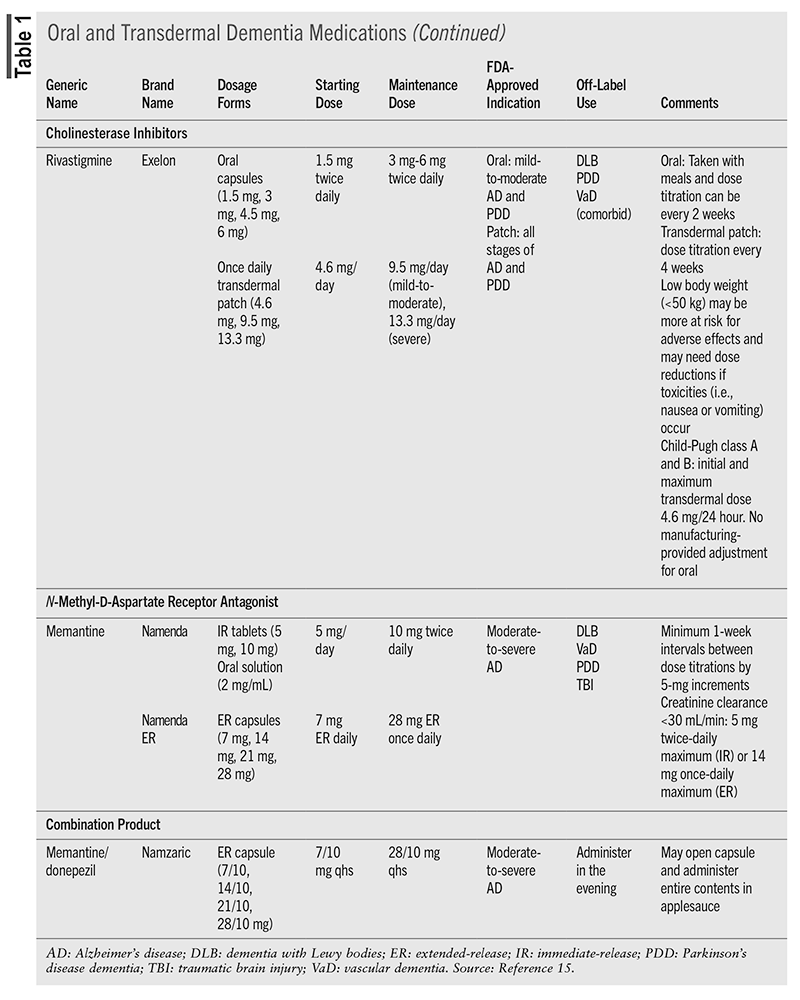

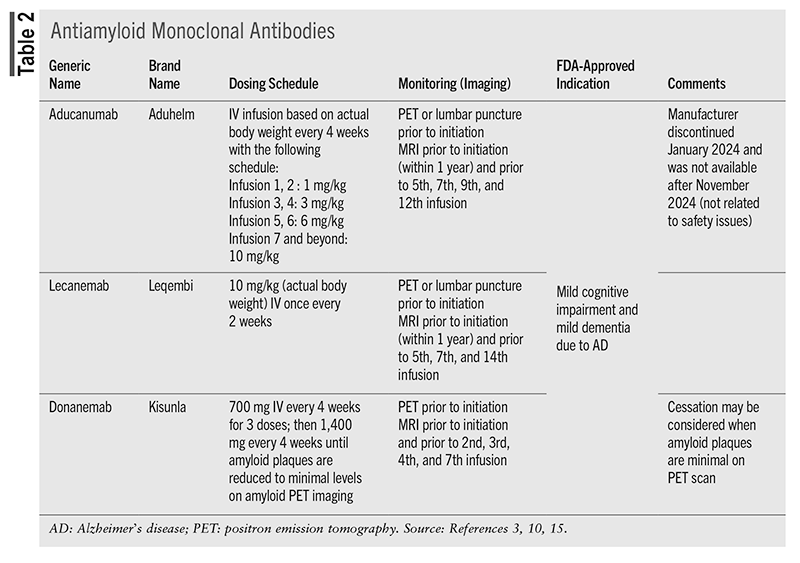

Treatment of AD dementia will depend on the cause and the staging. The primary benefit of intervention is to treat the symptoms of cognitive decline and neuropsychiatric symptoms.3,10,12 For cognitive decline, there has been long-standing use of cholinesterase inhibitors (CIs) and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist memantine.3 Recently approved immunomodulators target the neuropathologic features of AD to decrease brain amyloid β levels and have been shown to reduce decline in cognition after 18 months of treatment.12 TABLE 1 and TABLE 2 include information about these medications.3,10,15

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

CIs have been the backbone of dementia treatment for more than 2 decades and benefit the patient in the long and short term.10,12 CIs degrade acetylcholinesterase, which results in increased levels of acetylcholine—a critical neurotransmitter to the neurons involved in cognition.16 Benefits of CIs include reduction in symptom severity, cognition improvement, activities of daily living improvement, and, for patients with severe dementia, a reduction in mortality.12,16,17 The response to CIs may be varied, however, and may be impacted by stage of disease, rate of progression, signs of cholinergic deficit, presence of apathy, concurrent diseases, and education level.12 There have been some comparisons of the CIs to each other, and a difference in cognition or behavior outcomes between agents was not found.16

The three medications in this class, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, come in a variety of formulations and have slightly different indications. All CIs require dose titration due to the high rate (up to 50%) of gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events that can occur with initiation and each dose titration. Nausea, vomiting, and/or diarrhea typically lasts 1 week after dosing adjustments; however, the GI effects can lead to dehydration, loss of appetite, and weight loss.10,15 Oral rivastigmine has been associated with the highest incidences of GI effects compared with the other agents.18 Adherence is essential to develop tolerance to these effects; if a patient misses more than 2 days of medication, he or she may have to restart at the initial dose.10

Another potentially limiting adverse effect is CIs’ risk for hypertension and conduction abnormalities (bradycardia, atrioventricular block, prolonged QT interval, and torsades de pointes).15 Heart rate can decrease 5 to 10 beats/minute and can be problematic for frail older adults and those on β-blockers. In addition, CIs have been linked to falls, fractures, and unnecessary pacemaker placement.10 Skin reactions may occur with patch products.15

NMDA Antagonist

Memantine is the sole agent approved in this class and works to partially block the NMDA receptor.16 This will inhibit glutamate (an excitatory neurotransmitter) from causing additional damage to neurons.10 Memantine can be used as monotherapy or in combination with CIs, but it is indicated only for moderate-to-severe forms of dementia. To be efficacious, the target dose needs to be reached. The titration schedule can be cumbersome owing to weekly titration adjustments, but titration packs are available.10

Memantine is generally well tolerated, with confusion, drowsiness, dizziness, and headache being the most common adverse effects.10,15 However, there have also been reports of impaired consciousness, sleep disturbances, seizure, agitation, and hallucinations, so patients and caregivers should be aware of the potential for neuropsychiatric effects.15

Deprescribing

If a patient has been on a CI or memantine treatment for longer than 12 months and experiences no benefit (improvement, stabilization, or rate of decline decreased) at any time during therapy, experiences worsening cognition and/or function over 6 months, or has severe or end-stage dementia, discontinuation of medication(s) is recommended. Discontinuation should be a trial with close monitoring (e.g., 4 weeks), and if the patient has clear worsening after the withdrawal, the medication should be reinitiated. Both CI and memantine should not be abruptly stopped; there should be a step down through available dose formulations that occur every 4 weeks to the lowest available dose, followed by cessation. Other instances that may warrant a trial discontinuation include a decision by the patient with dementia or the family/caregiver, the patient with dementia refuses or is unable to take the medication, or nondementia terminal illness.19

Antiamyloid Monoclonal Antibodies

Immunomodulators targeting β-amyloid plaques, a hallmark AD feature, have been studied for decades but have not shown consistent evidence of clinical efficacy until recently.3,10 These agents work to decrease amyloid levels (evaluated by amyloid positron emission tomography [PET]) below the levels considered to be abnormal by breaking the amyloid down for clearance.3,10 Aducanumab was the first medication to receive accelerated approval by the FDA in 2021; however, after November 2024, it was no longer available in the U.S.3,10 Lecanemab and donanemab received full FDA approval in 2023 and 2024, respectively, and have been shown to slow the rate of decline by 27% to 47% in several cognitive and functional measures compared with placebo in patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild AD.3,20,21 These trials were 18 months in duration, but given these medications’ disease-modifying effect, there remain questions about their cumulative benefit with long-term treatment.22

Prior to initiation, patients must have documented β-amyloid pathology (via amyloid PET scan or with CSF test) and an MRI to assess risk for amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), which are their primary adverse effect.3,10 ARIA is further classified as having edema (ARIA-E) or hemorrhage (ARIA-H) and is a boxed warning for medications in this class.15 The risk for ARIA is higher in patients who are apolipoprotein E4 homozygotes; therefore, testing prior to initiation is recommended. ARIA can be asymptomatic, therefore routine MRI monitoring is required; or the patient may be symptomatic and present with headache, confusion, seizures, or focal neurologic signs.3 These changes are reversible with medication discontinuation, and depending on the level of symptoms and the severity of MRI findings, the medication may be continued or held until MRI evaluation indicates resolution.10,15 There is no dosing adjustment recommended for renal or hepatic impairment.15

Controversy regarding the β-amyloid monoclonal antibodies relates to the modest benefit, frequent administration and monitoring, significant adverse effect risk, price (lecanemab costs $26,500 per patient per year), and limited patient population that would be similar to the patient populations of the clinical trials.12 Determining their clinical value in light of these limitations is difficult.3

Treatment of Non-AD Dementias

Except for rivastigmine in PDD, there are no medications with FDA approval for non-AD dementias; however, several are used off-label (TABLE 1). For DLB and PDD, the CIs donepezil and rivastigmine have the best evidence to support the treatment of cognitive symptoms. Memantine may have some benefit, but additional studies are needed.23 For vascular dementia, the CIs have been used, with donepezil having the greatest benefit on cognition, but evidence is weak.24 Memantine has also been evaluated for vascular dementia, but prevention of repeat cardiovascular events is currently the best intervention.10 FTD pathophysiology is different than other dementias, which limits treatment. CIs and memantine are not recommended, as they were associated with no improvement in cognition or worsening cognition, respectively, and both had a worsening of behavioral symptoms.25 Oxytocin has been evaluated with some positive effect in FTD.3,26

Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia

More than 90% of those who are diagnosed with dementia will eventually develop neuropsychiatric symptoms.1 In fact, these symptoms may be the presenting symptoms.3 Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of dementia are noncognitive symptoms, also sometimes referred to as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, and are observed in all dementia subtypes.1,3 The symptoms may be difficult to distinguish from comorbid psychiatric disorders that may also be present. Furthermore, symptoms may include apathy, psychosis (delusions, hallucinations), aggression, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, socially inappropriate behaviors, and agitation.3,6,27

Agitation and aggression are most reported in FTD, while depression is the most frequent NPS in vascular dementia.1 Anxiety occurs most often with DLB, and apathy is reported most frequently with AD.1 These symptoms often result in increased caregiver burden and stress and increased nursing home placement frequency.6 NPS in AD have also been reported to be associated with decreased quality of life, higher degrees of functional impairment, and a faster cognitive decline.28 Apathy may lead to less independence for the patient and a greater need for assistance with activities of daily living.28

Dopamine agonists utilized to treat Parkinson’s disease can result in impulse-control issues and should be evaluated as a cause of NPS.28 Some behavioral difficulties may be manifestations of pain and may be ameliorated with the scheduled administration of acetaminophen or other pain relievers. This may be particularly true in a patient who is unable to verbalize or with limited communication. Other potential causes of behavioral concerns should be considered, including urinary tract infections, pneumonia, constipation, and medication causes (e.g., anticholinergics).1,6

Medications to treat neuropsychiatric symptoms should be reserved when all other nonpharmacologic interventions are unsuccessful.28 Agents such as CIs or memantine utilized for cognitive symptoms should be continued, even if medications for NPS are initiated.3 If the patient is already receiving medications for neuropsychiatric symptoms, current regimens should be examined for efficacy, and if they are determined to be ineffective, discontinued.3

Medications should be used cautiously to treat symptoms because of the risk of side effects, particularly the risk of falls and the potential worsening of cognition.3 An additional risk of instituting pharmacologic intervention for NPS is that these medications have the potential to worsen symptoms via side effects (i.e, medication causing GI symptoms might agitate a patient).3 Modest evidence for efficacy exists for atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, but significant safety issues exist with their use.3 If atypical antipsychotics are utilized, the lowest dose and shortest duration of time of therapy are recommended.1 Other medications that have been used to treat NPS include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and benzodiazepines, despite a lack of evidence of efficacy.3

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics carry a black box warning in patients with dementia; however, they may still be used, particularly when symptoms such as agitation and aggression remain despite nonpharmacologic approaches.3 In 2005 the FDA issued a warning regarding the increased risk of death associated with second-generation antipsychotics in patients with dementia. Cardiovascular events (heart failure, sudden death) and infection (pneumonia primarily) were the most commonly observed causes of death.1 This warning was revised in 2008 to include first-generation antipsychotics as well, as they were found to carry a similar or potentially higher risk than second-generation agents. Risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, and quetiapine have all been studied in randomized clinical trials, with varying results.1

Antipsychotics (olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) were found to be no better than placebo for the primary or the secondary outcome in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness–Alzheimer’s Disease (CATIE-AD). The primary outcome was time to discontinuation for any reason, and the secondary outcome was the Clinical Global Impression of Change scale.1 Cognitive decline was also observed in this trial in those who were treated with antipsychotics compared with placebo, and this effect has been observed in other meta-analyses of antipsychotics to treat NPS.1 Long-acting injectable antipsychotics are not recommended for NPS unless there is a chronic comorbid psychotic condition present.1 In 2023, brexpiprazole became the first agent approved in the U.S. for the treatment of agitation associated with AD despite continued questions about safety and efficacy in clinical trials of AD.30

Other Agents

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are first-line in treating mood-related and anxiety symptoms, although their overall efficacy remains unclear.31 Benzodiazepines should be utilized with extreme caution, as they may increase the risk of falls and contribute to confusion, sedation, and delirium. Benzodiazepines may also accelerate cognitive decline. Disinhibition and tolerance may also be observed if benzodiazepines are utilized in patients with dementia.6 Methylphenidate has been used in a single study to specifically treat apathy associated with AD.29 Valproic acid has been traditionally utilized for agitation and aggression; however, concern about lack of efficacy and significant side effects have called its use into question.6

Many agents have been or are being investigated for treatment of agitation associated with AD, including pimavanserin (currently approved only for psychosis associated with Parkinson’s disease), dextromethorphan/quinidine, dextromethorphan/bupropion, prazosin, cannabinoid agonists, and dexmedetomidine.32

Conclusion

Dementia is an ever-increasing diagnosis, particularly in those aged older than 65 years. Pharmacists can contribute to the care of patients with dementia in many ways. They can assist with controlling modifiable risk factors (e.g., treatment of hypertension, obesity) and screen the medication profile of older individuals for agents that could impact cognition (e.g., anticholinergics). Pharmacists can provide detailed information during counseling about the titration requirements, the importance of adherence as it relates to adverse effects, and what to do in cases of missed doses. Additionally, pharmacists can assist with deprescribing and educate patients and family members or caregivers about the benefit versus risk of second-generation antipsychotics in persons with dementia.

REFERENCES

- Tampi RR, Jeste DV. Dementia is more than memory loss: neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia and their nonpharmacological and pharmacological management. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(8):528-543.

- CDC. Alzheimer’s disease dementia facts and figures. www.cdc.gov/alzheimers-dementia/about/index.html. Accessed October 15, 2024.

- Reuben DB, Kremen S, Maust DT. Dementia prevention and treatment: a narrative review. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(5):563-572.

- Alzheimer’s dementia. Alzheimer’s Association. www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures. Accessed October 15, 2024.

- Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and management of dementia: review. JAMA. 2019;322(16):1589-1599.

- Pless A, Ware D, Saggu S, et al. Understanding neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: challenges and advances in diagnosis and treatment. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1263771.

- National Institute on Aging. National Institutes of Health. What is dementia? Symptoms, types, and diagnosis. www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-and-dementia/what-dementia-symptoms-types-and-diagnosis. Accessed October 17, 2024.

- Sadowsky CH, Galvin JE. Guidelines for the management of cognitive and behavioral problems in dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:350-66.

- Prajjwal P, Marsool MDM, Inban P, et al. Vascular dementia subtypes, pathophysiology, genetics, neuroimaging, biomarkers, and treatment updates along with its association with Alzheimer’s dementia and diabetes mellitus. Dis Mon. 2023;69:101557.

- Mahan RJ. Dementias. In: Sanoski CA, Witt DM, eds. Pharmacotherapy Self-Assessment Program, 2024 Book 3. Neurology and Chronic Conditions. Lenexa, KS: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2024:35-47.

- Wilbur J. Dementia: dementia types. FP Essent. 2023;534:7-11.

- Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet. 2024;404:572-628.

- Fox C, Smith T, Maidment I, et al. Effect of medications with anti-cholinergic properties on cognitive function, delirium, physical function and mortality: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):604-615.

- 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052-2081.

- Lexi-Drugs. Hudson, OH: Lexicomp. http://online.lexi.com/. Accessed October 2024.

- Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:379-397.

- Xu H, Garcia-Ptacek S, Jonsson L, et al. Long-term effects of cholinesterase inhibitors on cognitive decline and mortality. Neurology. 2021;96:e2220-e2230.

- Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Webb AP, et al. Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(2):211-225.

- Reeve E, Farrell B, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in dementia: guideline summary. Med J Aust. 2019;210:174-179.

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21.

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527.

- Peterson RC, Aisen PS, Andrews JS, et al. Expectations and clinical meaningfulness of randomized controlled trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(6):2730-2736.

- Taylor JP, McKeith IG, Burn DJ, et al. New evidence on the management of Lewy body dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):157-169.

- Battle CE, Abdul-Rahim AH, Shenkin SD, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for vascular dementia and other vascular cognitive impairments: a network meta-anaylsis. Cochrane Database System Rev 2021;2(2):CD013306.

- Gambogi LB, Guimaraes HC, de Souza LC, et al. Treatment of the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia: a narrative review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2021;15(3):331-338.

- Huang M, Zeng B, Tseng P, et al. Treatment efficacy of pharmacotherapies for frontotemporal dementia: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2023;31(12):1062-1073.

- Gerlach LB, Kales HC. Pharmacological management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):489-507.

- Cummings J, Lanctot K, Grossberg G, Ballard C. Progress in pharmacologic management of neuropsychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2024;81(6):645-653.

- Clark ED, Perin J, Herrmann N, et al. Effects of methylphenidate on neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from the ADMET 2 study. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;9(3):e12403.

- FDA. FDA approves first drug to treat agitation systems associated with Alzheimer’s disease, May 11, 2023. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-drug-treat-agitation-symptoms-associated-dementia-due-alzheimers-disease. Accessed October 29, 2024.

- Li J, Ebrahimi AH, Ali AB. Advances in therapeutics to alleviate cognitive decline and neuropsychiatric symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(10):5169.

- Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Pract Neurol. 2022; June:40-44.